We work with communities in addressing complex social-ecological challenges through research, capacity building and creating spaces for dialogue and knowledge exchange.

Contact usLatest news

Rights of Wetlands Review

The Rights of Wetlands Review is a working document that introduces Rights of We ...

Colombo wetland management framework

A key output of the ‘Increasing the resilience of biodiversity and livelih ...

Metro Colombo urban wetland status report

The Metro Colombo urban wetland status report reviews the progress made since th ...

Community’s right to grow

Supporting community food growing has become an important mechanism for deliveri ...

Urban wetlands improving the wellbeing of city dwellers

In a participatory video made by the community of the Mulleriyawa wetland in Col ...

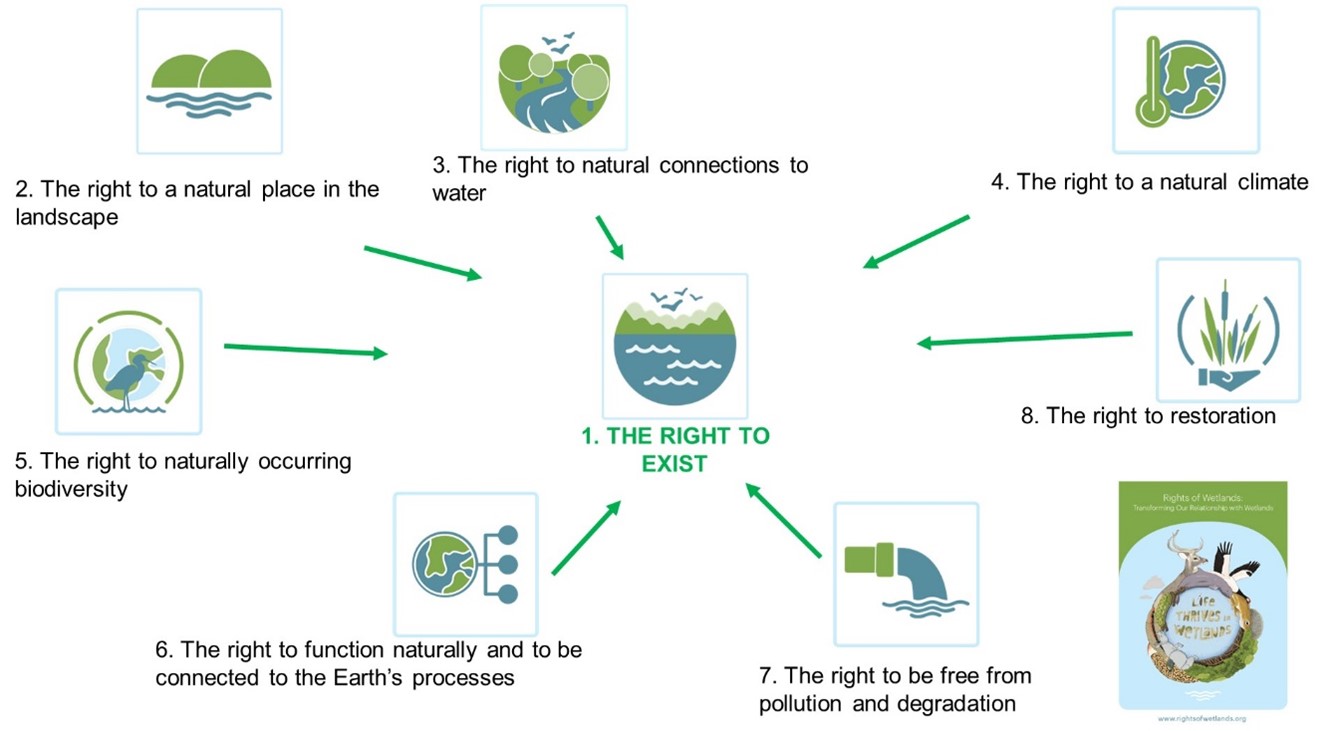

What is a Rights of Wetlands approach?

Rights of Nature is gaining increased support as a solution, an approach that is ...